Ethiopia. Ancient Abyssinia. Birthplace of Arabica coffee. (I really wish I could do an intro to this blog post narrated by David Attenborough.) What a magnificent place.

The harvest in Ethiopia this year looks to be small - about 30% less than last year from what we heard. Many places experience bi-annual cycles, where one year will have a large crop and next year a small crop, so nothing unusual about it. At least a lower yield quite often mean higher taste quality, but it's hard to predict until you're done processing and drying.

Casper and I spend a little over a week in Ethiopia with the primary goal to visit Yukro and spend a good amount of time with the people there. Last year we bought one lot from them, which was our first purchase from Ethiopia since the famed Idido (Aricha micro lots). It's a coffee that has impressed us immensely once we got the roast right, and it's holding up extremely well over time too. So we are very eager to cup the coffees from Yukro again this year and have every intention of buying again (and in the future) provided that the quality maintains. After visiting we have no doubt that it will actually improve. The energy there and the knowledge that is being implemented will surely make the coffee from Yukro stand out in the future too.

Just as we arrived at Yukro village, the members were gathered for a meeting. We were asked to share our thoughts on their coffee and give them sort of a pep talk. We don't think they needed a pep talk at all, and it was awesome to feel the spirit and energy there.

Vis Farms på et større kort

Vis Farms på et større kort

One disclaimer though: We were there too early. See, these kind of trips we have to plan a long time in advance, as both of us have a pretty full work week as it is. Casper is in charge of our roastery and deliveries and I run our wholesale, marketing and training. So we had been told that the week we went would most likely be the top of the harvest (and still early) and planned accordingly. Unfortunately the harvest became delayed and we were there just about a week before the actual harvest began. Bummer. The upside, though, was that the people at Yukro actually had time to talk with us and show us around. During harvest that can be a problem, as everybody is really busy.

Yukro is actually a small village as well as being the name of the wet mill. The members of the cooperative wet mill (also called a washing station) lives in the area around the village. Last year Yukro had around 250 members. This year it has increased to 367 members. It cost 400 birr (the Ethipian currency) to become a shareholder of the coop. The members elect a cooperative committee or board of 13 people, including a chairman, vice chairman, treasurer and secretary. The chairman os Yukro is Mr.

Taddase Gudina (on the left on the picture below). A very friendly and welcoming man, who invited us into his home and shared many meals with us. In general the hospitality and openness of the Ethiopians is amazing.

Much like in Kenya the members (shareholders) pick their own coffee trees and deliver cherry to the wet mill. Here they get a receipt (in triple copies) for the amount of cherry they've delivered and are paid cash straight away. The cherry price is set by the board of the coop before the harvest begins, so the members know what to expect. When the coop has sold all their coffee and know how much is left after paying off loans, salaries etc. the dividend is paid out. This actually happened while we were there, meaning more than half a year after we bought the coffee. The reason for it being so late is that all the accounting needs to be finished first, and some of the last of the coffee hadn't been paid until quite late.

The Yukro coop is only two years into operation. The farmers around have been growing coffee for many years selling the cherries to private millers or exporters. By having their own wet mill they get much more value directly to themselves. The wet mill was set up initially by an American NGO (Non-Governmental Organization) called Technoserve. Funded by the Bill Gates foundation the organization works to transform lives by providing poor people access to productivity-enhancing tools. Building washing stations in Ethiopia is part of that. Technoserve does an amazing job in helping the farmers - with out having any agenda to make profit (as you might know, an NGO can't make money). They provide knowledge about growing and processing as well as helping the coops manage their finances and get better deals. It's really the kind of work we believe can help places like Ethiopia: Private businesses that thrive and bring money to the local community. Rather than one-off feel-good charity projects, we wish to be part of a longer lasting business relationship where all parts are profitable and equal. If you haven't already clicked the link above to Technoserve's website, I'd recommend you click now and read through it.

Mr Moata Raya, who's an agronomist at Technoserve in Jimma, took time to go with us to Yukro and show us around. He's a fun guy, always really cheerful with a great sense of humour, and at the same time very knowledgeable about coffee and the difficulties facing farmers. He also helped translate for us on a number of occasions, as we don't speak any Oromic or Amharic (they have around 85 different languages in Ethiopia).

At the Nordic Roaster Forum professor Giorgio Graziosi, from the University in Trieste, Italy, gave a very interesting lecture, that I'd recommend you see here and download the slides. Especially slide 20 is pretty mind blowing. Him and his colleagues are working on mapping the DNA of coffee, which is a rather extensive work taking several years. By now they can map out different varieties according to their genes. So for example they can determine based on DNA if a certain variety really is a geisha, caturra or whatever. In their work they have mapped coffees from several places, but what really surprised them was the coffee from just two places in Ethiopia. The variation in the gene pool there was astounding. If you look at Slide 20 you can see that the diversity in varieties from just those two places is great than all the other varieties grown commercially around the entire world.

This great diversity stems from the fact that Ethiopia is still pretty much the only place in the world where coffee is growing wild. There's thousand of different varieties growing in forests and farms there that no one knows what is.

Walking around the wild forests surrounding Yukro it's clear to anyone that this is not a plantation, as you know if from other coffee producing countries. Literally every tree we'd walk past looked like a new variety. And it was easy to pick out. One had huge, broad, round leaves and the next had narrow, thin, pointy ones. One had oblong, huge cherries and the next completely round little bombs. There were dwarf varieties next to tall, thing ones. And so on and on. You don't need to be an expert to see the differences here.

The other thing that strikes you is how wild the forest grows. From a distance you would not be able to tell that the main crop there was coffee. It just looked like a rain forest to us. Walking into the woods it actually took me a little while before I realized that some of the tall trees were coffee. There were several 10 meter tall coffee trees there!

To pick it the farmers have to drag the top down with a long stick to reach the cherries. Fortunately the stem is pretty flexible and the tree doesn't suffer. I hope the picture catches how tall this tree is, but it'll never do the actual sight justice. It was impressive.

Walking around the farms you couldn't help notice very strong smells from different herbs, especially wild mint growing like weed in the forest bottom. They don't spray the trees for anything here (pesticides or herbicides) and doesn't use any artificial fertilizers either. Everything is organic. They do weed out the bottom of the forest and let nature handle the rest.

We think the great bio-diversity and multiple varieties help that deceases and pests don't spread as easily as when you have just one variety of coffee growing across a big area. It's common sense within other agricultural products, so why would coffee be any different? This raises some interesting thoughts as specialty coffee these days is often sold and marketed as single varieties and we in general (us included) want to taste a specific variety on its own. But the mixture of varieties might have a much better impact at origin, and the wildness you also get in the cup is to us equally interesting as a single variety. In any case,

At the Yukro wet mill the cherry is received and then processed. Using an eco-friendly depulper and demucilator called Penagos 1500, both the pulp and the mucilage is removed.

After pulping and demucilating the coffee goes into soaking tank overnight. Early in the morning they take it to skin drying tables, which are always totally shaded. If it's taken direct to sun the parchment will crack and the coffee dry too quickly. On skin drying tables they are also sorting out any visible defects. Here the coffee is 3-4 hours, then moved to regular drying tables, where they keep sorting.

Waste water from processing (which is very little compared to for example processing in Kenya) is cleaned with Magic Grass, which absorbs the honey water in its root system. Water flows naturally through the magic grass which absorbs most of it and the rest goes into a sediment pool, where the water vaporize.

Optimal drying time for the coffee at Yukro is 8-10 days on raised tables that are shaded when there's sun, but not when cloudy. 10,5-11% drying green is ideal and the dry mill will only accept between 9-11,5%.

After drying its taken to storage. Here they weigh and label it with lot number and which table it's been dried on. They keep it in open bags for conditioning to let excess heat escape for about a day. When it's a whole lot (150 bags) it's taken to a warehouse with Oromia union next to the Dry Mill.

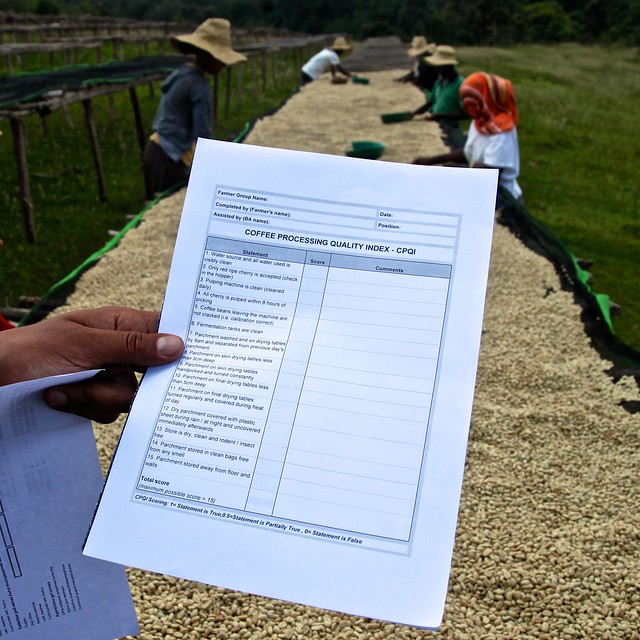

Check list for Coffee Processing

The Oromia Coffee Farmers Cooperative Union is based in Addis Ababa, with their HQ right next to their new Dry Mill. It was taken into operation two years ago and is the cleanest dry mill I've ever seen. Brand new destoners, hullers and density and size separators and sorting machines. Finished with a very efficient hand sorting space. That final hand sorting is a big part of the final clean cup and definitely worth paying the extra money for.

In a few weeks we can expect to cup the first samples of the lots from Yukro. From there it's still a little while before the fresh crop has been through the dry mill and are ready for export. Hopefully everything will ship on time and we'll again be one of the first roasteries to offer fresh Ethiopian coffees. But Ethiopia is a tricky country and time and time again roasters have seen their containers full of fresh coffee sitting in a warehouse of being stuck at a port for weeks, due to different circumstances beyond their control (for example there were a general strike last year just after our container shipped). So you never really know. In any case we're already looking forward to cup this years lots and continue our relationship with Yukro.

If you haven't already viewed our slideshow of pictures from the trip click this link.

No comments:

Post a Comment